Your friendly magazine photo editor wants to know if you have an aerial photo of Crestone Peak. Or maybe you are just curious about the stuff you photograph out an airplane window. Looking at a map, a topographic map, or a satellite image is the usual way to identify objects in an aerial photo, but sometimes that doesn’t work very well. That’s where Google Earth in 3D “flyover” mode comes in.

Originally posted Feb. 8, 2017. Updated Feb. 11, 2017.

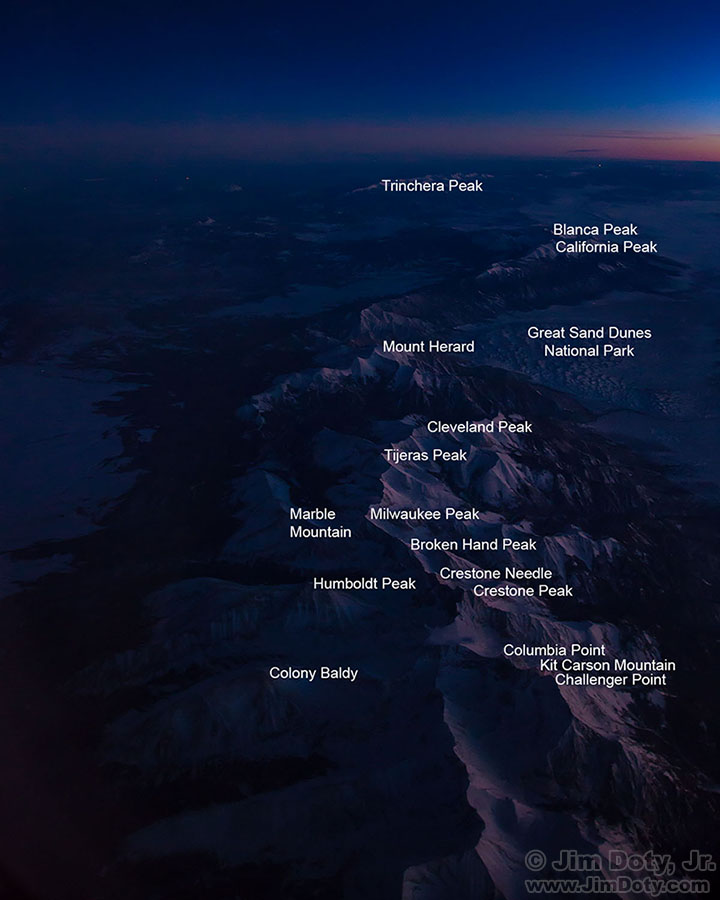

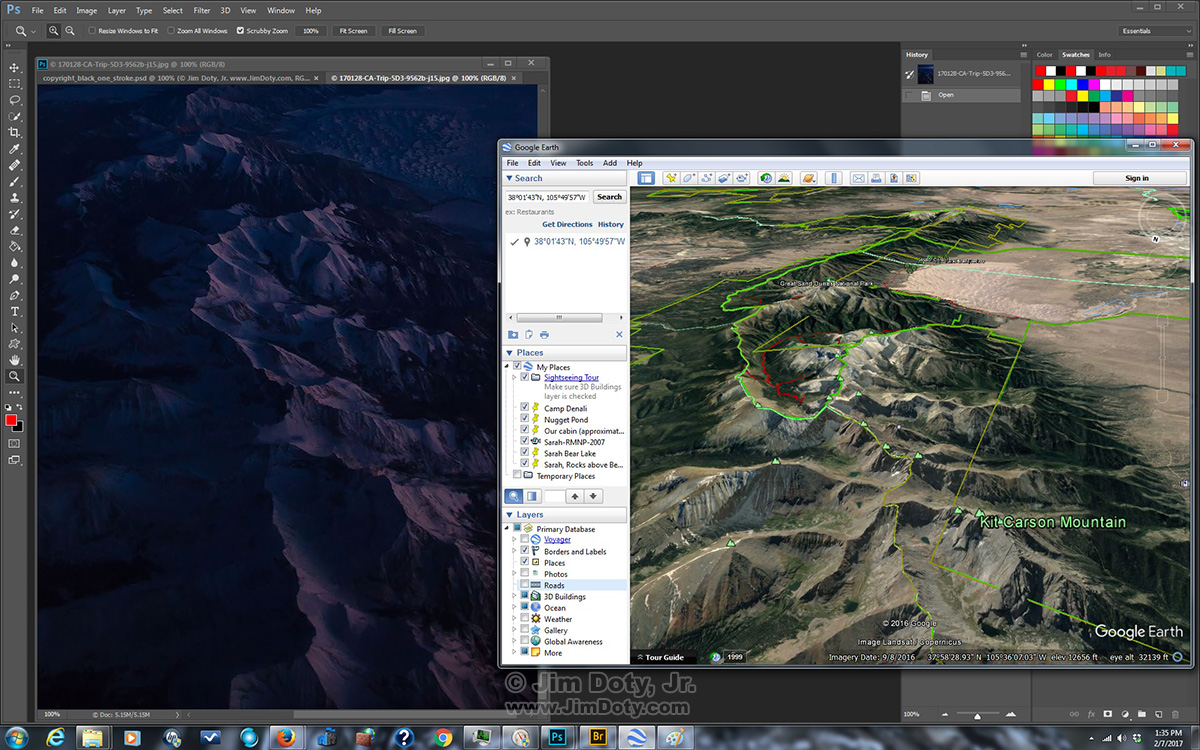

Photo and Google Earth Satellite Image: Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the Great Sand Dunes. Click for a larger version.

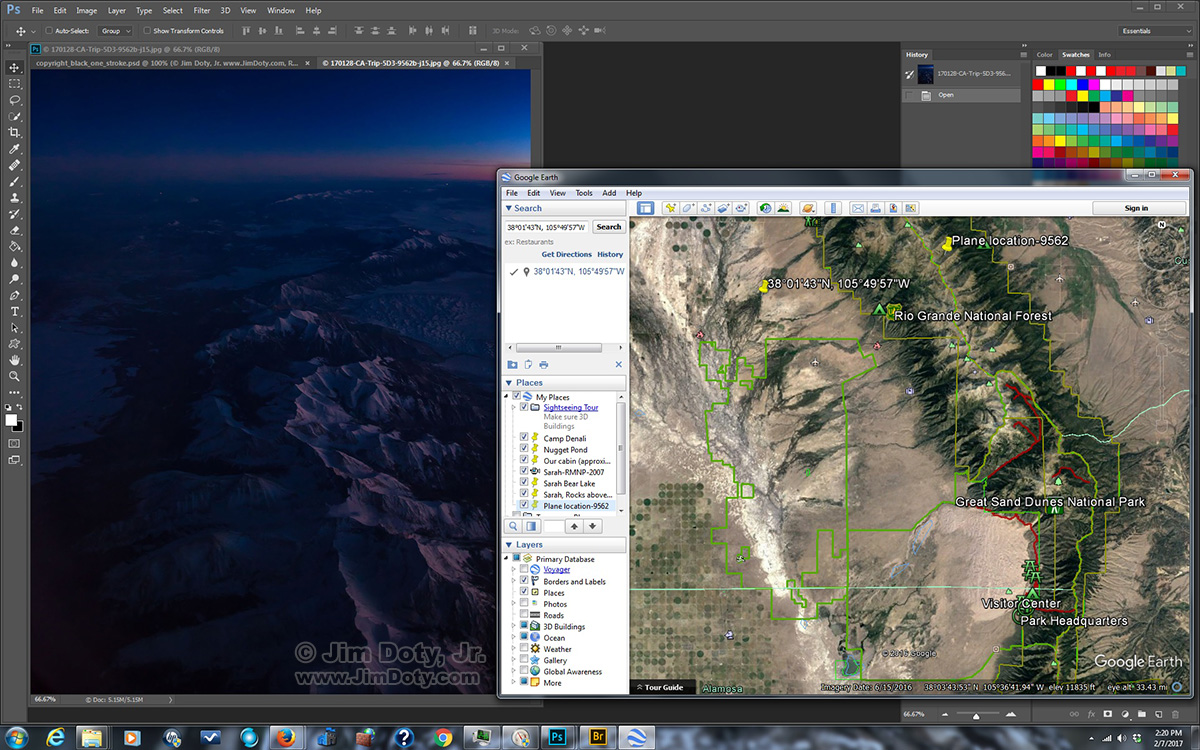

The problem with satellite images is the straight down view. It works fine for cities, or in this example the Great Sand Dunes, but a straight down look at mountains and other natural land forms can be a jumbled up mess because everything is flattened out and the mountain all start to look pretty much the same. How do you figure out which mountains on the right correspond to the mountains in the photo on the left? It is made more complicated by north being at the bottom in the photo and at the top in the satellite view. I generally decided labeling mountains and other land forms was more trouble than it was worth. Google Earth 3D mode changed all of that by making the whole process much easier, much faster, and more accurate.

FYI: The upper left yellow pin in the Google Earth image marks the supposed GPS location of this photo but this is off thanks to “GPS lag” with a GPS unit separate from the camera. The GPS unit on the camera was even farther off. You can’t always trust GPS coordinates when you are in an airplane. More about using GPS in airplanes in this article. The top center pin is the approximate location of the plane when I took the photo.

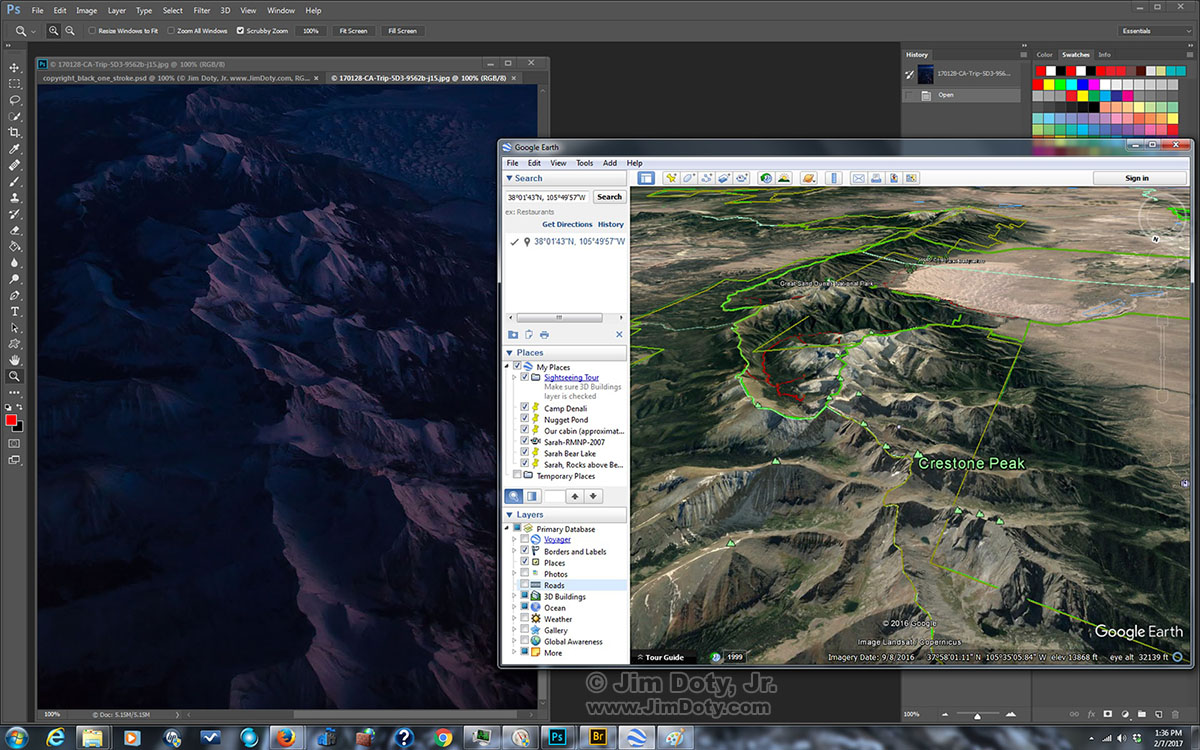

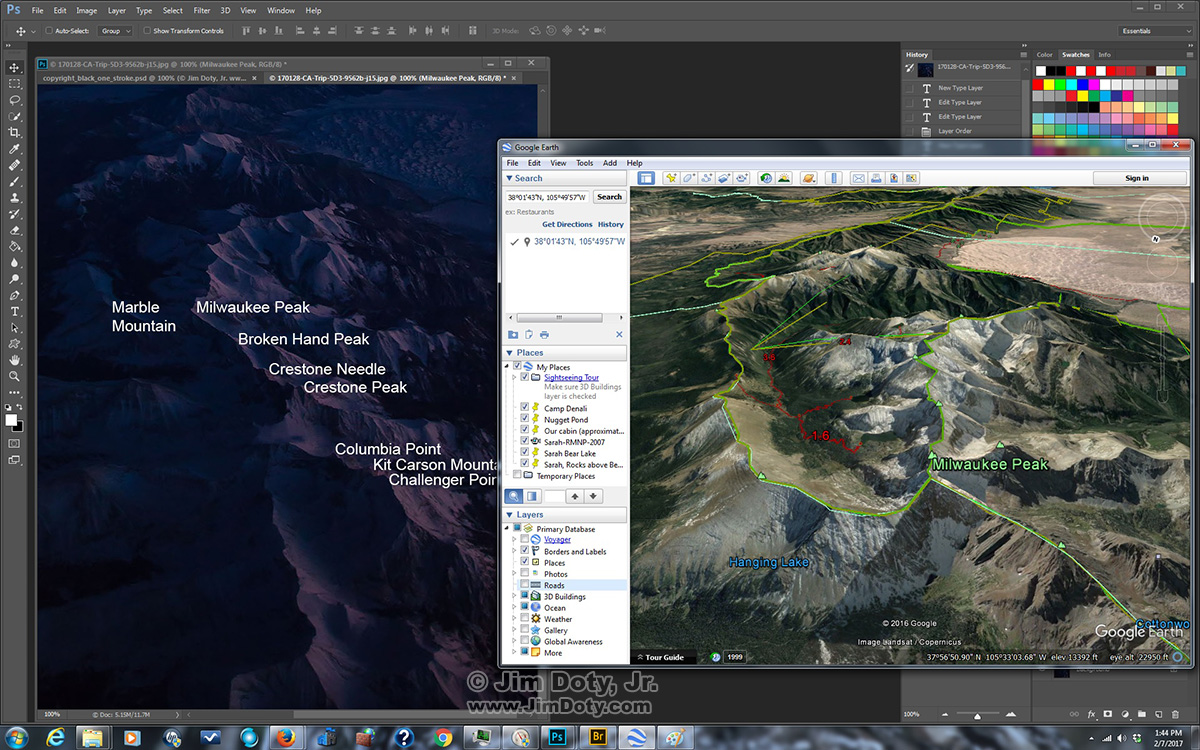

Photo and Google Earth: Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the Great Sand Dunes. Click for a larger version.

By using the control arrows and the slider in the upper right corner of Google Earth you can rotate and angle the image to get a simulated 3D view similar to what you would see from an airplane. Note the eye altitude (in the bottom right corner) has been set to match the approximate altitude of a plane. The directional circle (upper right, marked with an N for North) has been angled to match the SSE view from the airplane window. From this view is it much easier to figure out which mountains are which. In the camera photo there is a prominent C shaped mountain range below the sand dunes. This become very obvious in the angled 3D Google Earth view.

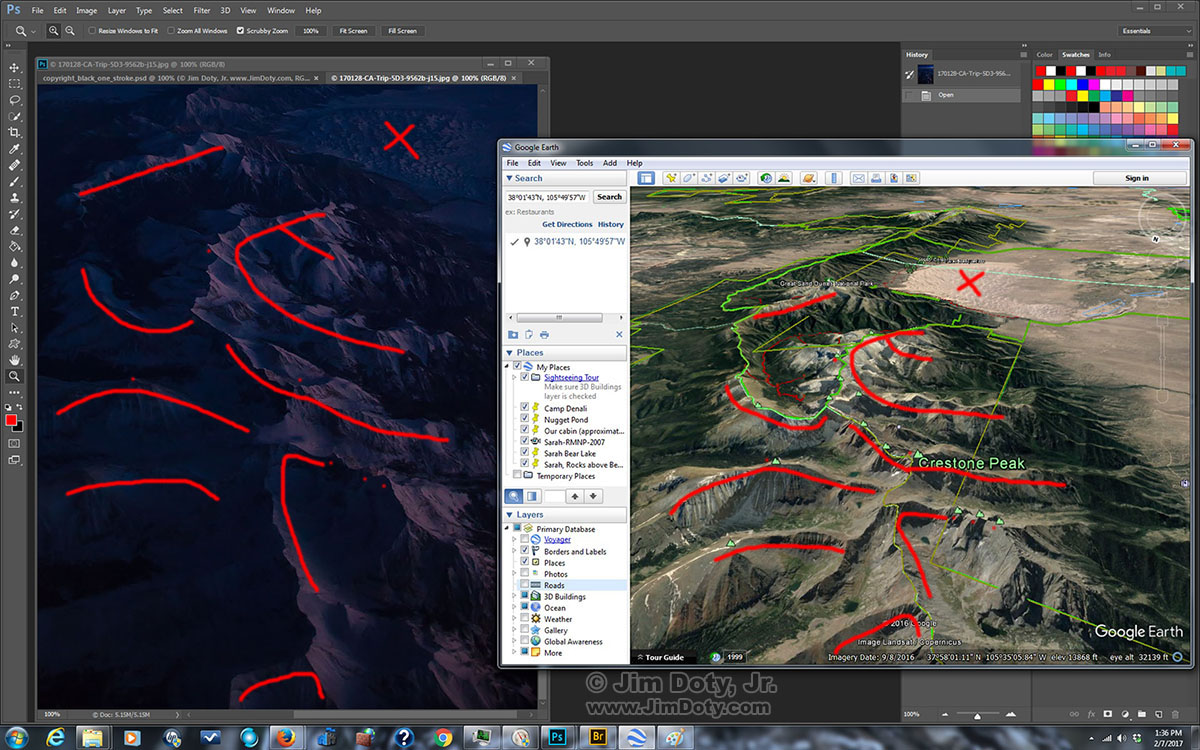

Photo and Google Earth: Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the Great Sand Dunes. Click for a larger version.

For comparison’s sake, I marked the sand dunes with an X, some of the obvious ridges with lines, and a few obvious mountains with red dots. There are little green mountain symbols on some of the Google Earth peaks. If you hover over each green symbol with your cursor the name of the mountain pops up. In this case the cursor (which does not show in this screen capture) was over Crestone Peak. I have a red dot marking Crestone peak in the photo.

Photo and Google Earth: Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the Great Sand Dunes. Click for a larger version.

One by one I picked each mountain with a green symbol, figured out the name in Google Earth (in this example, Kit Carson) and typed the name on the corresponding peak in my photo.

Photo and Google Earth: Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the Great Sand Dunes. Click for a larger version.

As I worked my way up the photo from bottom to top I would fly up (south) in Google Earth and zoom in on each mountain (Milwaukee Peak) to be sure the identification was correct. If you are new to Google Earth, it will take a while to get used to the controls so you can fly around an image like you are in an airplane.

Google Earth images are actually “flat” satellite images looking straight down, not 3D images, so how do they do it? The clever folks at Google use altitude data for all the points in the image to create the simulated 3D view. If you zoom in really close (to a low altitude) you will see some distortion of the image like these weird, semi-flattened, left-leaning trees on a mountainside. That is what happens when you take a flat image and warp it to create a 3D image. But the distortion is a small price to pay for the huge advantages to having a simulated 3D view.

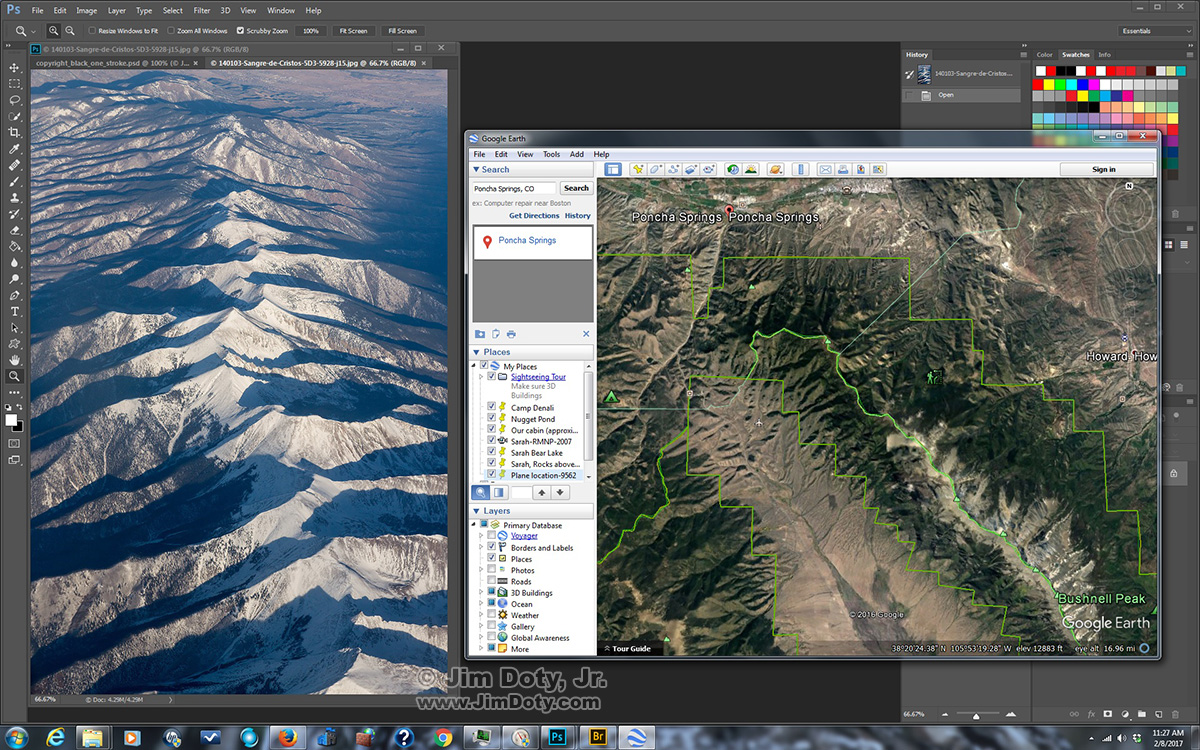

Photo and Google Earth: Northern Sangre de Cristo Mountains and Poncha Springs, Colorado. Click for a larger version.

This is an aerial photo from Mount Bushnell (lower right) to Poncha Springs, Colorado (top) along with the corresponding satellite image. This is another photo that would be time consuming to label accurately from a straight down satellite image.

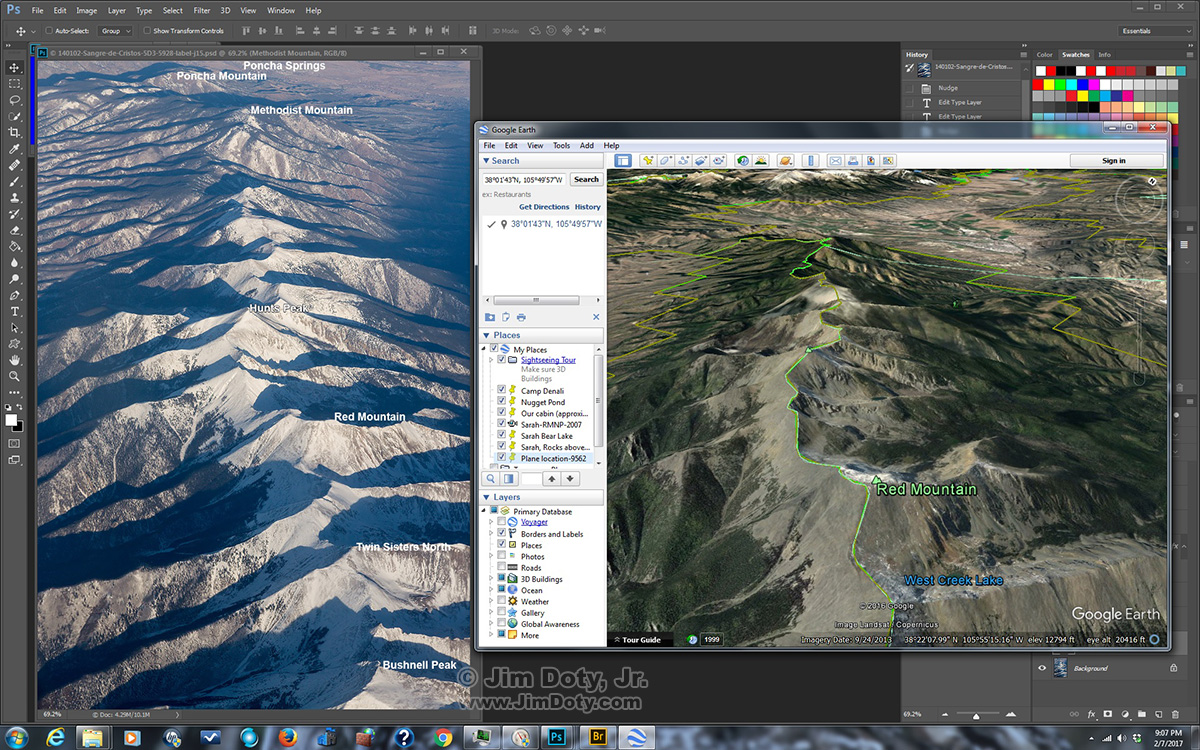

Photo and Google Earth: Northern Sangre de Cristo Mountains and Poncha Springs, Colorado. Click for a larger version.

Using the controls in Google Earth to simulate the 3D angled view from an airplane and zooming in makes identifying the mountains much easier.

For identifying a lot of natural land forms (even if you aren’t in a plane), Google Earth in 3D mode is your best friend. It is a free download for your computer, tablet, or smart phone.

And after you take your pwn aerial photos of the Sangres and label them using Google Earth, when that photo editor calls and asks if you have a photo of Crestone Peak for the front cover of a magazine, you can confidently say, “Yes, I do!”

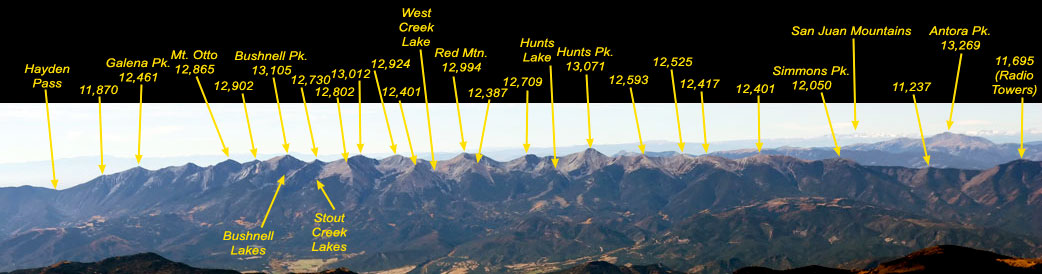

The Northern Sangre de Cristo Mountains by Wojtek Rychlik. See the link below for more of his Colorado mountain range photos. Click for a larger version.

GPS Series Links

“How To” Series: Using GPS in Photography – An Overview

“Where Were You When You Took Those Photos?â€

The Why and How of Adding GPS Information To Your Photos

How To Get GPS Coordinates Into Google Earth

Checking the GPS Location Accuracy of Your Camera, Part One

Checking the GPS Location Accuracy of Your Camera, Part Two

Comparing the GPS Accuracy of Three Cameras

Using Google Earth to Find the Name of a Mountain (and How to Get GPS Info Into Google Earth)

Geotagging Aerial Photos: The Joys and Frustrations of Using GPS on an Airplane

Using Google Earth in 3D Mode to Label Aerial Photos

Satellite Communicators: The GPS Messaging Devices That Can Save Your Life

Geotagged Photos: Posting Photos Online Can Put Your Family at Risk

Related Links

How to Photograph from a Plane at Dusk (The Sangre de Cristo Mountains)

How to Process Aerial Photos with ACR

Google Earth – the official download site

Aerial Photos of the Colorado Rockies by Wojtek Rychlik of Pikes Peak Photo.