Irena Sendler, a Catholic social worker, saved 2500 Jewish children from the Nazi death camps during WWII. Like Schindler, she kept a list. She hoped to reunite the children with their parents after the war. Unfortunately, most of the parents had been killed at Treblinka. She was captured by the Gestapo and tortured but she never gave up the names of her helpers or the children. Sentenced to death, a guard was bribed and she escaped. With a new name, she went back to her work. She died in 2008 at the age of 98.

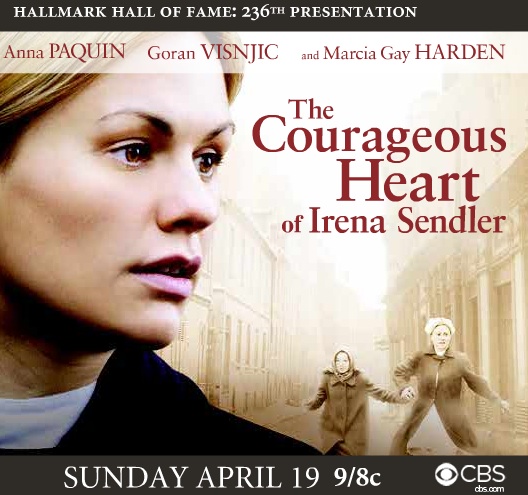

Her story is a Hallmark Hall of Fame presentation tonight. Hopefully, it will be posted here for later online viewing. The movie is adapted from the book The Mother of the Holocaust Children†by Anna Mieszkowska.

You can learn more about Irena Sendler here and here and here.

The article at the above link is reproduced below.

*** ***

Mother of Warsaw’s Holocaust children dies

Published: May 14, 2008

A Catholic social worker credited with saving over 2,500 Polish Jewish children from Nazi death camps during World War II has died at 98.

Irena Sendler was tortured by the Gestapo for her work and sentenced to death but escaped and continued her work. She was a member of Zegota, the code name for the Council for Aid to Jews and took charge of its children’s department wearing a nurses uniform and Star of David to enter Nazi-run holding areas to deliver food, clothes and medicine, including a typhoid vaccine.

After it became clear that Jewish children in the ghettos would be sent to the Treblinka death camp, Zegota decided to try to save as many children as possible.

Using the codename “Jolanta”, Sendler became part of an escape network: one baby was spirited away in a mechanic’s toolbox; some children were transported in coffins, suitcases and sacks; others escaped through the city’s sewer system. An ambulance driver who smuggled infants under stretchers in the back of his van kept his dog on the seat beside him, having trained the animal to bark to mask any cries from his hidden passengers.

In later life Sendler recalled the heartbreak of Jewish mothers having to part from their children: “We witnessed terrible scenes. Father agreed, but mother didn’t. We sometimes had to leave those unfortunate families without taking their children from them. I’d go back there the next day and often found that everyone had been taken to the Umschlagsplatz railway siding for transport to the death camps.”

The children rescued by Sendler were given new identities and placed with convents, sympathetic families, orphanages and hospitals. Those who were old enough to talk were taught Christian prayers and how to make the sign of the Cross, so that their Jewish heritage would not be suspected.

Like the more celebrated Oskar Schindler, Sendler kept a list of the names of all the children she saved, in the hope that she could one day reunite them with their families.On the night of October 20, 1943 her house was raided by the Gestapo, and her immediate thought was to get rid of the list. “I wanted to throw it out of the window but couldn’t, the house was surrounded by Germans. So I threw it to my colleague and went to the door. There were 11 soldiers. In two hours they almost tore the whole house apart. The roll of names was saved due to the great courage of my colleague, who hid it in her underwear.”

The Nazis took Sendler to the Pawiak prison, where she was tortured; although her legs and feet were broken, and her body left permanently scarred, she refused to betray her network of helpers or the children whom she had saved. Finally, she was sentenced to death.

She escaped thanks to Zegota, one of whose members bribed a guard to set her free. She immediately returned to her work using a new identity. Having retrieved her list of names, she buried it in a jar beneath an apple tree in a friend’s garden. In the end it provided a record of about 2500 names, and after the war she attempted to keep her promise to reunite the children with their families. Most of the parents, however, had been gassed at Treblinka.

Sendler was born Irena Krzyzanowska in Warsaw into a Catholic family. Her father was a physician who ran a hospital; a number of his patients were impoverished Jews. He died of typhus in 1917, but his example was of profound importance to his daughter, who later said: “I was taught that if you see a person drowning, you must jump into the water to save them, whether you can swim or not.”

After the war, she continued in her profession as a social worker and also became a director of vocational schools. In 1965, she became one of the first Righteous Gentiles to be honoured by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem. At that time, Poland’s communist leaders would not allow her to travel to Israel, and she was unable to collect the award until 1983.

In 2003, she was awarded Poland’s highest honour, the Order of the White Eagle; and last year she was nominated for the Nobel peace prize, eventually won by Al Gore. A play about her wartime experiences, called Life in a Jar, was written in 2000 by a group of American schoolgirls, and was performed in the US, Poland and Canada. She was also the subject of a biography, Mother of the Children of the Holocaust: The Story of Irena Sendler. Last year it was reported that her exploits in Warsaw were to be the subject of a film, starring Angelina Jolie.

In her latter years, Sendler was cared for in a Warsaw nursing home by Elzbieta Ficowska, who in July 1942, when six months old, had been smuggled out of the ghetto by Sendler in a carpenter’s workbox.